Farmers need innovative new varieties to stay ahead of changes in growing environments, and Corteva Agriscience seed breeders are there to help.

The new soybean variety Jason Denning is planting has been through quite a journey – one that has honed the bean’s yield and enhanced its potential.

Denning is a fourth- generation farmer who raises cattle and, as a Corteva Agriscience seed production grower, he helps grow what goes into the bags of seed other farmers plant. It’s a practice his father started back in the 1970s or 1980s – far enough back that Denning isn’t sure about dates – and one he’s kept up.

Across those decades, the Denning father and son team has worked with their trusted advisors to select fields, determine the right rotations, match expected yield to the number of available bins on the farm, and make sure those bins and all the equipment that feeds them are clean and ready to go.

Today, seed breeding is a five- to seven-year process, and Chandler needs to be certain that he’s breeding for the traits farmers will need when the new hybrid gets to market.

Good genes

That work was done by people like Michael Chandler, Northern Corn Research Lead for Corteva. He and his colleagues are the folks who bring new seeds to the marketplace, continuing a process that began nearly 100 years ago when Henry Wallace started selling hybrid seed corn, before founding Pioneer Hi-Bred (which has evolved to become the flagship seed brand from Corteva) two years later.

The company Wallace founded has provided generations of farmers with ever-improving seed corn, soybean seed, and more – with hybrids and varieties made better each year through selective breeding and biotechnology.

For corn seed, he’ll set up isolation so that stray pollen won’t drift in. “You’re probably looking at 640 feet,” Denning says. “You have to keep the genetics of what you’re growing pure.” After all, a lot of work went into getting them just right.

Jason Denning is a fourth-generation farmer and a Corteva Agriscience contract grower.

That’s something Corteva ensures by putting seed breeders out in the fields where they can talk to farmers and commercial partners alike.

They’re listening for “trait weaknesses… and what secondary traits are important for a given region,” Chandler reports. Why secondary? Because the first and most important

attribute is – and always will be – yield. The art comes in achieving that in a variety of conditions, especially temperature stress and drought, across maturities.

“If you’re a breeder in Ontario, Canada, you’re trying to select for good northern leaf blight tolerance and tolerance to Gibberella (ear mold) and, at the same time, keeping that yield level where it needs to be and homing in on your maturity.”

Just a few hundred miles away in Fargo, North Dakota, a breeder will be looking for entirely different traits,namely tolerance to brittle snap and Goss’s wilt.

Related article

Gene editing: bearing fruit in 2024

As crops with novel properties appear in farmers’ fields and the first gene-edited foods...

Picking parents

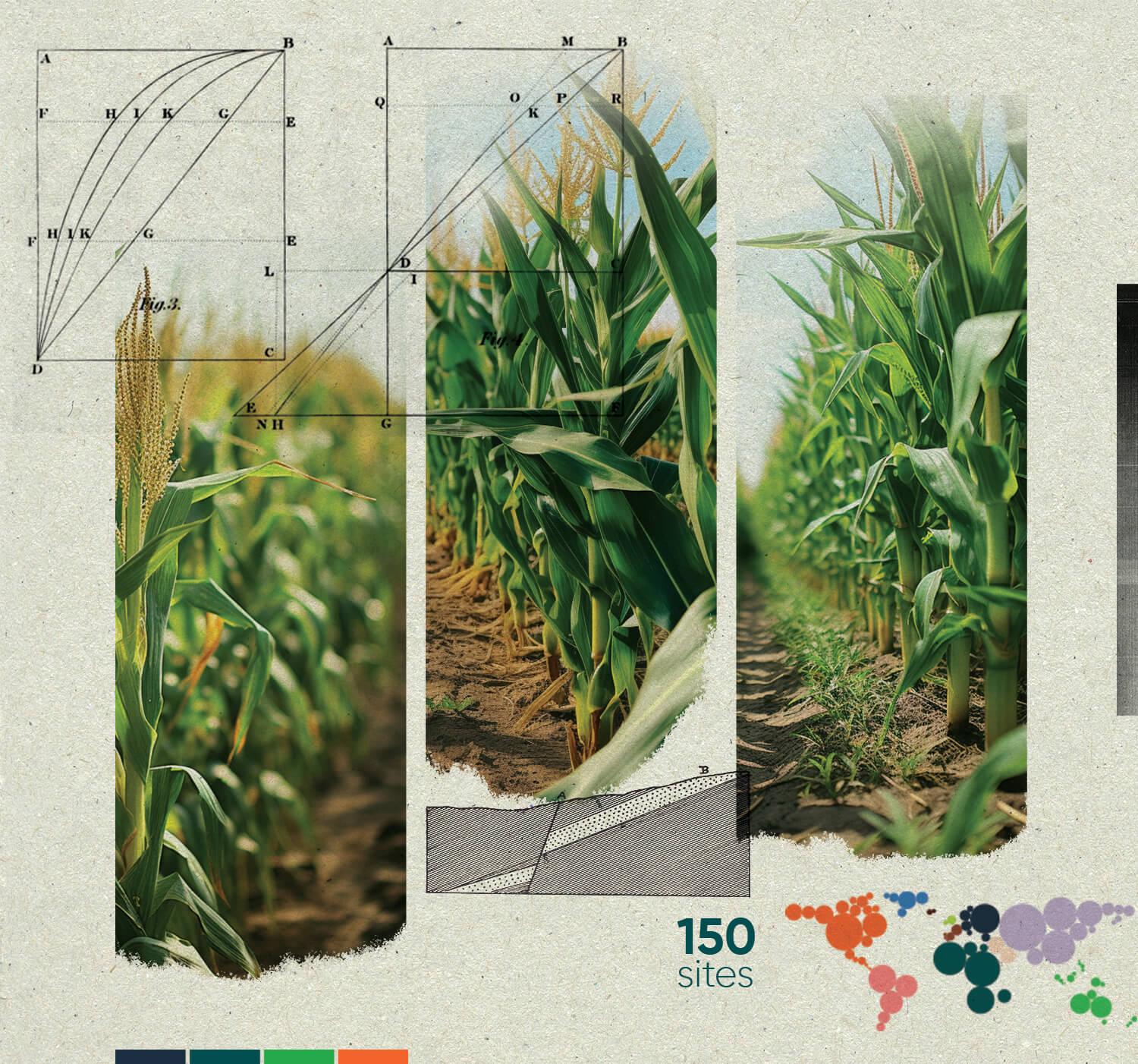

Effective seed breeding is, at its heart, a talent for selecting parents. “Our selection process is a big funnel,” says Chandler. “You start at the very top with a large set of genetics [in seeds], and then as you move down the funnel, every stage is a year of evaluation.”

He starts by selecting plants from the huge library of traits and genetics in Corteva’s best-in-class collection of germplasm – hundreds of thousands of digital molecular profiles. “We’ll select that down to around 10,000 entities,” Chandler says, which Corteva will grow for seed. With every step, he’s looking for “the positive attributes that one parent has and combining them with some other attribute that another parent has,” he says. “You pair strengths and weaknesses.”

The art of corn breeding is to combine high-yield performance with other desirable traits that will help solve problems for farmers.

Source: Corteva AgriscienceThe best 1,000, perhaps, will make it into the field for a breeding program: “There’s 70 seeds, 30 inches apart, in a two-row plot that’s 17 ½ feet long. For early germination testing, that’s what we consider an experimental unit, and that same experimental unit would also be in 30 other growing environments.”

At each site, tens of thousands of unique hybrids are being tested side by side, representing a range of hybrid programs. Many of those hybrids won’t survive the comparison to the reference commercial hybrids already being sold.

“Say 5% of those top 1,000 will be worth bringing forward, and those that advance could be screened in 60 environments by the middle stages of hybrid testing,” Chandler notes.

By the late stages of testing, there will be just a handful of hybrids left as candidates for commercialization, which Corteva will test in hundreds of growing environments.

There’s yet another layer of complexity – “inbred performance,” to use Chandler’s term. As he and his colleagues sift through the most promising hybrids, they also have to consider how much the parent plants yield. If they aren’t robust producers, it can raise the cost of producing the hybrid to unaffordable levels – hybrid and parent performance are not necessarily correlated.

Given that dizzying array of factors, it’s no surprise that “when you get to the very end of the pipeline – what we’re willing to actually commercialize and sell – that’s the most elite fraction of the genetics that you started with,” he says.

A new hybrid is born

Remember Jason Denning – the Corteva Agriscience contract grower? This is the moment when he enters the picture. Corteva works with Denning and scores of other seed production growers to raise seed for sale. Corteva starts with introductory volumes for the first year, working with what Chandler calls “target growers” to carry out larger strip trials.

With every year you get a different set of challenges. Having the right seed helps.”

“There’s nothing worse than commercializing a product on too many acres, only to find out that there was a stronger trait to be had or a trait weakness we didn’t know about before,” he admits.

Generally, in the second year, Denning and other seed production growers are in full commercial production as more and more farms pick up the new hybrid. Seed production growers welcome the new seeds. After all, as Denning says: “With every year, you get a different set of challenges: disease, weather, and more. Having the right seed – quality seed – helps.”

He’s focused on seed innovation and sees it as a way to stay ahead of changes in the field. Corteva is focused on innovation – and investing heavily in it – for the same reasons: plant diseases and pests evolve constantly, weather patterns change, and farmers’ needs develop accordingly. As a seed production grower, Denning gets to be on the forefront of that innovation, which he sees as the most important topic of all.

“The business we’re in is keeping things growing as population numbers get higher,” he says. “For us to do that, there has to be innovation.”

Seeds of Growth

It takes teams of scientists and farmers years of hard work to bring a new seed trait to market. Let’s go on the journey of a seed:

- Corteva’s network of field breeders work closely with farmers and commercial partners to uncover emerging problems and needs.

2. Armed with that intelligence, researchers use molecular profiles and modeling to trawl through millions of elite germplasm lines to predict which

parent plant characteristics might produce the traits farmers desire.

3. Researchers in nurseries around the world weed out underperforming plants, eventually arriving at around 1,000 different new varieties to try.

4. Seeds for those trials join tens of thousands of other candidates in arrays of experimental units at 30 growing sites.

5. The next year, the top performers move on to largerscale trials at 60 sites, and the year after that, the top 30 or so will be evaluated at 150 sites. Winners are chosen and move into commercialization.

6. Commercial growing begins with a small number of targeted seed production growers for the first year. Generally, by year two, commercial seed production is in full swing, and a new seed is out there helping farmers maintain high yields amidst changes in growing environments and new challenges.